For the first time, proteins have been identified in the structures of the inner ear of fish from millions of years ago, scientists report in the journal Scientific Reports.

The team led by Professor Jarosław Stolarski, director of the Institute of Paleobiology at the Polish Academy of Sciences, studied otoliths of fish from 14 million years ago. Otoliths are calcium carbonate structures found in the inner ear of fish. They are related to the perception of gravity and linear acceleration.

The team undertook the study to find out if the exceptionally well-preserved otolith fossils contained protein residues. The researchers also wanted to see if these proteins would be similar to those found in today's fish.

Professor Stolarski said: “Our research is the first paleoproteomic research, i.e. research involving the identification of proteins that occur in fossilized, not today's, otoliths.”

He added that although otoliths are made of calcium carbonate, they are of biological origin. The body significantly influences their formation.

Stolarski continued: “This influence is mainly through a particular type of protein released into the space where otoliths form. These proteins affect the shape and size, as well as the crystallographic variety of the mineral. Each species of fish has a different shape of otoliths, which suggests that the proteins influencing the formation of otoliths are also slightly different in different species.”

He explained that the main challenge was that organic ingredients inherently decompose over time “so when started our research, it was not clear whether any protein residues would be preserved.”

He added that they can only be preserved in conditions perfectly isolated from the external environment, like mammoth tissues in permafrost in Siberia for several thousand years. In the case of the studied otoliths, millions of years have passed.

He said: “We selected otoliths from sites where the fossil material is present in water-impermeable clays. And it paid off!.”

The research method consisted of removing the mineral part of the otoliths by dissolving it in dilute acetic acid. The residue is then lyophilised to remove residual solvents.

The next step is the identification of protein components with mass spectrometry coupled with liquid chromatography.

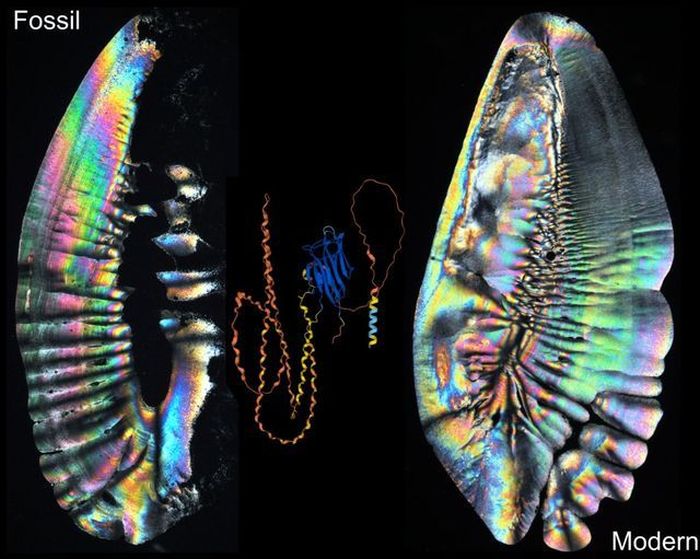

Stolarski said: “In our research, we used otoliths of both fossil and today's phycid hakes (genus Phycis), thanks to which we could compare the percentage of proteins preserved in fossil otoliths.”

He added that it was possible to identify 132 proteins in the otoliths of today's fish and only (or as many as) 11 proteins in the otoliths of fossil fish.

The researcher explained that the research results allow to access biological information about ancient organisms.

He said: “Although DNA has no chance of surviving that long (it usually lasts about 2 million years), we have shown that identifiable protein fragments can survive much longer under specific conditions. The fact that we have identified some proteins that are similar or even identical to those found in today's otoliths shows that the biomineralisation process itself has not changed significantly in these fish.”

Professor Jaroslaw Stolarski plans to continue the research.

Find out more in the source article HERE. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Krzysztof Łapiński

krx/ bar/ kap/

tr. RL